Home game: Re-thinking Canada through Indigenous hockey

Published: May 23, 2019

ŌĆ£Damn, we got it. We won one in their barn!ŌĆØ

To Cree hockey player Eugene Arcand, these words made little sense. You see, in the 11 years he had skated for two Saskatchewan Indian residential schools ŌĆō as sweater number 14, residential school number 781 ŌĆō no settler teams had ever visited the dilapitated outdoor rinks at residential school in Duck Lake or the in Lebret.

It wasnŌĆÖt until he was 23, when Arcand became the only Indigenous player in the regionŌĆÖs Intermediate AAA hockey league, that he learned from settler teammates that ŌĆ£home iceŌĆØ is supposed to be ŌĆ£an advantage.ŌĆØ

We ŌĆō Mike Auksi (Anishinaabe/Estonian) and Sam McKegney (white settler of Irish/German descent) ŌĆō are researchers with the . We interviewed Arcand in Kingston, Ont., as part of our networkŌĆÖs preliminary work to cultivate critical understandings of hockeyŌĆÖs role in relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

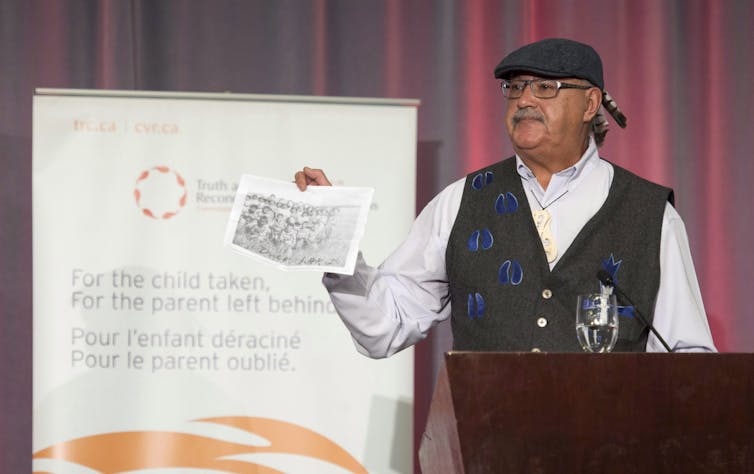

Arcand, whose Cree/▓į┼¦│¾Š▒├Į▓╣Ę╔┼¦Ę╔Š▒▓į name is aski kananumohwatah and whose is 380, knows what itŌĆÖs like to be denied the right to play in a ŌĆ£home barnŌĆØ in his traditional territory of . He was a member of the Truth and Reconciliation CommissionŌĆÖs (TRC) and has been in support of Indigenous sport in Saskatchewan and across the country.

As such, he understands hockey as a site of prejudice, but also as a site with potential for positive change.

ŌĆśWe didnŌĆÖt ever get to socializeŌĆÖ

Regimentation, discipline and control were at the core of residential school design, as a means of conditioning Indigenous children to shed their cultural values. , says Indigenous studies scholar Braden Te Hiwi of the University of British Colombia and sport historian and sociologist Janice Forsyth of Western University, also an IHRN researcher.

Exactly how sport curricula were used varied over time and territory, as well as along gender lines, during more than 100 years of residential schooling in Canada.

Where they were present, sports like hockey were built into the institutionsŌĆÖs social engineering regime as what University of Ottawa health researcher Michael Robidoux calls a ŌĆ£.ŌĆØ

Yet, the experiences of Indigenous players were not confined by institutional objectives or the goals of individual overseers. Forsyth and historian Evan Habkirk, also of Western University, argue that sports helped many students ŌĆ£make it through residential schoolŌĆØ by being a forum in which they could develop .

As Cree residential school survivor Philip Michel explained in a talk he gave at : ŌĆ£We were told we were no good in residential school. But in hockey, we were good. We were just as good as anybody. In many cases, we were better.ŌĆØ

Arcand recalled his teammates showcasing their skill against settler teams at tournaments. However, their experiences differed dramatically from those of the non-Indigenous kids: ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖd put all our equipment on at the school and get on the bus and weŌĆÖd go to whatever town ŌĆ” and weŌĆÖd play sometimes three games in one day. After each game, weŌĆÖd get back on the bus ŌĆ” We didnŌĆÖt ever get to socialize against our opponents.ŌĆØ

Years later, Arcand asked a former supervisor from the residential school, ŌĆ£ŌĆśWhy would you make us wear our equipment all day like that? Other kids got to undress. Other kids got to run around the rink. And we didnŌĆÖt. We had to wear our same stinky equipment all day long.ŌĆÖŌĆØ The supervisor replied, ŌĆ£ŌĆśSo you wouldnŌĆÖt run away.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Project to assimilate

In an 1887 memorandum to cabinet, , prime minister and minister of Indian Affairs, identified the ŌĆ£great aimŌĆØ of the Indian Act legislation as being to ŌĆ£.ŌĆØ

Contradictions, however, persisted at the heart of this legislation. When residential schools were at their peak, policies like on the Prairies actively prevented Indigenous people from integrating into settler society. While residential schooling was ostensibly about absorption, contemporary policies enacted barriers to inclusion by restricting mobility.

In ArcandŌĆÖs segregation from the settler teams, we see a similar contradiction at play. Residential schools were intended to condition Indigenous youth to self-identify not as Indigenous but as Canadian ŌĆō with hockey functioning as a marker of such identification.

Yet the Indigenous players at the tournament were treated as second-class citizens, forbidden from fraternizing with the other players.

The governmentŌĆÖs political goal of eliminating Indigenous rights and identities was never accompanied by a similar commitment toward eliminating settler perceptions of Indigenous inferiority.

Assimilation, in Canada, has never meant equality.

Calls to action in sport

Another factor complicating Indigenous is the way .

The IHRNŌĆÖs early research suggests that hockey is linked to the . Hockey belongs to Canadians because it belongs in the Canadian landscape, so the story goes. Thus, participation in the game allows settlers to imagine they belong here, too ŌĆō with adverse implications for Indigenous people.

Arcand remembers the ferocious nature of anti-Indigenous racism in Saskatchewan hockey in the 1970s. So much so, he shares, that when his teamŌĆÖs trainers packed up the sticks after a road game, theyŌĆÖd leave his out for safety. ŌĆ£I had to use my stick to defend myself in those arenas.ŌĆØ

Anti-Indigenous racism persists in Canadian hockey today. In the past year, faced taunts of ŌĆ£savagesŌĆØ from spectators, players and coaches at the Coupe Challenge tournament in Qu├®bec. Five First Nations teams from Manitoba found themselves without a league to play in .

Yet teams, coaches, players and fans are not without the artillery to make positive change. The Final Report of the TRC provides guidance on Sport and Reconciliation.

The report calls for government-sponsored athlete development, culturally relevant programming for coaches, trainers and officials, as well as anti-racism awareness training.

Arcand has worked much of his life to eliminate barriers to participation in sport for Indigenous, racialized and economically challenged athletes. To truly foster inclusion, he says, hockey associations need to confront racism and settler entitlement through disciplinary actions with sufficient teeth to create conditions of safety.

ŌĆ£Why are the people in power,ŌĆØ he asks, ŌĆ£not stepping up to properly enforce excluding these people who deserve to be excluded from the sport?ŌĆØ

ŌĆśWe still need the gameŌĆÖ

Between 1975 and 1981, long before and other football playersŌĆÖ celebrated acts of protest, Arcand refused to stand for the Canadian national anthem. When told to do so during a playoff game, he responded, ŌĆ£ŌĆśCoach, you want me to stand up? IŌĆÖm going to get up and youŌĆÖll never see me again. Your choice. Make it right now.ŌĆÖŌĆØ The coach never bothered him again.

Years later, when the horrors of residential school were coming to light through the TRC, one of ArcandŌĆÖs settler teammates from those days embraced him at the World U20 Hockey Tournament in Saskatchewan. He told Arcand, ŌĆ£Now we understand.ŌĆØ

Arcand, a target of brutal assimilation policies and racist violence, says, ŌĆ£Sports saved my life, hockey saved my life.ŌĆØ

Provided Canadians reckon with hockeyŌĆÖs relationship to settler colonialism and racism, Arcand insists, ŌĆ£We still need the game.ŌĆØ![]()

is an indigenous research officer at the . is an associate professor of English language and literature at .

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .